People Are Starting to Care a Lot More About Capital Efficiency

The days of relatively easy, crazily cheap capital have gone for a while. So investors and directors, being rational folk, are now paying a lot more attention to capital efficiency, or how well businesses use their more expensive and less free flowing capital.

This attention typically comes in the form of a simple ratio that can be measured easily and reported in every Board paper. There are various ratios abound, with the common factor being some measure of profit on the top, and some measure of applied capital on the bottom, e.g. NOPAT/TIC.

This is fine. It rightly puts attention on capital cost, and it can be monitored at regular intervals. It’s also sort of how capital works at an enterprise level, where use of capital and realised profits are spread over time from multiple customers and products.

But it isn’t how capital works at an operational level, which is essentially a series of separate situations where an upfront outlay on product development or customer acquisition creates a payback over time. We need a mechanism to make good decisions about applying that operational capital. Enter customer lifetime value.

Customer Lifetime Value – What is it Good For?

Customer lifetime value, or CLV, nets off the upfront investment in acquiring and setting up a particular customer from the flow of profit you get from that customer over their life with you.

It’s being used increasingly as marketing is becoming a more data led profession, and is a go to tool for making decisions at an operational level. It’s simple to calculate if you have the data, and there are plenty of places showing you how.

It has some real benefits. Critically, it recognises the operational reality of upfront investment followed by stream of profit, that gets missed in Board meetings that look at monthly measures. It consequently stops your thoughts being dominated and fooled by regular measures like high gross profit that ignore offsetting issues such high cost of acquisition, or disloyalty and short lifetimes.

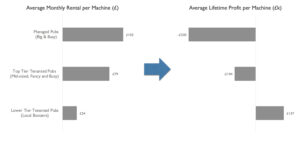

Here’s an example where CLV led a Board of a fruit machines company to do an about turn on who its best customers were, from high margin but disloyal flagship pub accounts to small, lower margin, loyal local boozers. Numbers are changed for confidentiality but proportions kept the same.

Customer Lifetime Value – Why Capital Cost Changes Everything

But CLV as it’s commonly practised has one real drawback, so simple and basic that I can only put it down to years of cheap and easy money. The drawback is that it totally, utterly ignores the cost of capital.

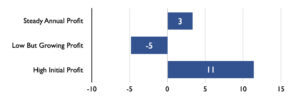

Here’s an example of CLV with 3 different profit streams that have the same 4 year total: one that’s flat, one that starts small and grows, and one that starts high and falls off.

They all have the same, nice high lifetime value.

But we’re totally ignoring the cost of capital here and the time value of money. This cost of capital is higher than you think it is, and much higher than you want it to be. It isn’t the 5-10% you can borrow at, unless you’re running a utilities monopoly. It isn’t even the 20% your VC backer needs as a promise to its funders, unless all you’re doing is the ultra low risk activity of selling the same stuff to identical customers. The cost of capital to use is the sum of two things: the risk of the initiative you’re undertaking plus the “risk free” cost of capital.

It’s very common for investors and senior managers to look for a 3 year payback on invested capital, which is about a 25% annual cost of capital, so I’m going to use that as typical.

Here’s what the customer lifetime value looks like in our 3 scenarios once we discount profit streams by 25% per year.

Customer Lifetime Value with 25% Cost of Capital

Only the initiative with high early profits has any material lifetime value.

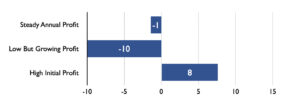

Now let’s add in a 5% uplift in cost of capital from a base rate rise.

Customer Lifetime Value with 30% Cost of Capital

Only the initiative with high early profits has any value at all. The one with the low early profits and the never-never year 3 uplift is highly value destroying.

Cards on the table, I’m not the first person to notice this. Economists 100 years ago noted that times of cheap capital prompted investment in more speculative and longer term paybacks. When capital goes up in price, it moves to ideas with higher, more immediate payback, and there’s creative destruction of the speculative ventures.

Conclusion – Stop Destroying Value & Pay Attention to the Cost of Capital

As capital becomes less free flowing and cheap, we need to be a lot more disciplined and think differently about investment decisions at an operational level as well as at Board level. With higher cost of capital, we need to refocus our attention on projects with nearer term value, and cut back many of those speculative projects with near term pain and long paybacks, at least until the cheap and free flowing days return.